|

|

|

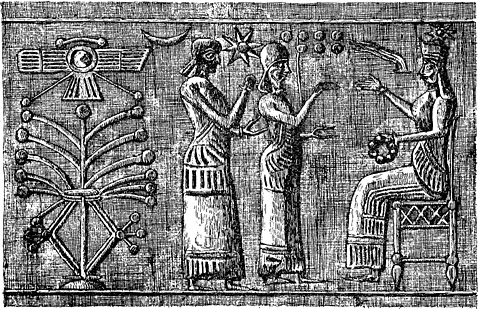

Babylonian Cylinder (From Landseer’s Sabæan Researches, page 263)1

Babylonian Cylinder (From Landseer’s Sabæan Researches, page 263)1

|

Albert Pike and the Zend-Avesta

|

|

|

Avestan language, also called (incorrectly) Zend language, eastern Iranian language of the Avesta, the sacred book of Zoroastrianism. Avestan falls into two strata, the older being that of the Gathas, which reflects a linguistic stage (dating from c. 600 BC) close to that of Vedic Sanskrit in India. The greater part of the Avesta is written in a more recent form of the language and shows gradual simplification and variation in grammatical forms. When the canon of the Avesta was being fixed (4th to 6th century AD), Avestan was a dead language known only to priests. It probably ceased to be used as an everyday spoken tongue c. 400 BC, but the sacred word was passed down through oral tradition. Avestan was written in a script evolved from late Pahlavi writing, which, in turn, derived from Aramaic. 3.

|

|

|

With no historical justification some writers have claimed Albert Pike actively participated in the Ku Klux Klan of the Southern Reconstruction era.

Among other claims, one of the more curious is the emphasis placed on Pike’s writings on Aryan themes. Pike wrote three books about a group of peoples living in an area stretching from Albania to Northern India some two to three thousand years ago.2.

These Indo-Aryans and Irano-Aryans —as Pike styled them— practiced a religion called Zoroastrianism taught them by Zaruthustra.

One of Pike’s books in particular appears to interest the current generation of Kluxers: his Indo-Aryan Faith and Doctrine as Contained in the Zend-Avesta, completed in manuscript form in 1874, but not transcribed and published until 1924.4. While Pike’s opinions on blacks and Jews are clearly racist, these, and his opinions of the Catholic church, Methodism and Northerners in general, clearly mark him as a product of his time and place but don't prove his association with the Klan. A distinction must be made between the study of these Aryan peoples and their beliefs, and the promotion of a 19th century theory on racial superiority termed Aryanism. Those Kluxers and anti-masons who hold up Pike as a Klan supporter fail, or refuse, to make that distinction.

ALBERT PIKE

What does Pike have to say? First, although Pike later taught himself Sanskrit and translated other works, in 1874 he relied on the translation of Darmesteter 5. and restricted himself to a critical review of the current thinking on the topic. Unfortunately many of the opinions voiced by both him and his contemporaries have since been discounted by subsequent research and archaeological findings. Pike never claimed any great authority for his opinions:

"It is to be a book chiefly of conjectures and suggestions. I make no pretensions to any critical knowledge of the Zend or Bactrian language, and have for the most part had, as aids to interpretation, only the English text, furnished by Bleek (from Spiegal) and by Dr. Haug, with notes accompanying their translations." [p. i.]

Pike also pleads for understanding and tolerance for the many different translations and interpretations of the Avesta :

"The fact that different scholars should differ in their interpretations, or that the same scholar should reject his former translation, and adopt a new one that possibly may have to be surrendered again as soon as new light can be thrown on points hitherto doubtful and obscure—all this, which, in the hands of those who argue for victory and not for truth, constitutes so formidable a weapon, and appeals so strongly to the prejudices of the many, produces very little effect in the minds of those who understand the reason of these changes, and to whom each new change represents but a new step in the advance of the discovery of truth." [p. 13.]

"Passages in the Veda or Zend-Avesta which do not bear on religious or philosophical doctrines are generally explained simply and naturally, even by the latest of native commentators. But as soon as any word or sentence can be so turned as to support a doctrine, however modern, or a precept, however irrational, the simplist phrases are tortured and mangled till at last they are made to yield their assent to ideas the most foreign to the authors of the Veda and Zend-Avesta." [p. 13.]

"I have not set out, either with any preconceived theory, or with any ambition to discover new meanings and interpretations. I am too well aware of my want of qualifications in the way of scholarship, to indulge, knowing naught of Zend and little indeed of Sanskrit—to indulge in any such inexcusable vanity and self-conceit." [p. 127.]

"We can never be sure that an obscure text of these old hymns has not been corrupted; or that particular words have not, before or after they were written down, lost their original meanings, and received derivative ones; or that their real meaning is not unknown, or supposed to be what it never was; or that there is not error in identifying a particular Zend word with a particular Vedic word, especially as the true meaning of so many of the latter is unknown. [p. 141.]

Having said this, Pike then proceeds to discount and depreciate the interpretations of the best scholars of his day, Haug and Spiegel among them, while pushing his own interpretations:

"Much of the translation of the Veda, by Wilson, Müller and Muir is conjectoral. How much more this is the case with the Zend-Avesta, the reader has already seen in part, and will yet have ampler evidence." [p. 141.]

"Etymological conclusions, based upon literal resemblances of words, are confessedly uncertain; and when to this is added, as in this case, scantiness of knowledge of Sanskrit and Zend, I cannot but have many misgivings as to the soundness of my deductions. But if the scholars fail to prove to me the meaning of a word, to my satisfaction, I must examine for myself." [p. 173.]

Pike describes Haug’s translations as "utter nonsense" [p. 197.] and frequently deprecates both Haug and Spiegler. On the many occasions that Spiegel is prepared to acknowledge a passage as being obscure or beyond his comprehension, Pike does not hesitate to give his own interpretation, labeling any other as specious or fatuous. [p. 504, 515, etc..]

"Dr. Spiegel, also failed to see, I venture to think, the real meaning of the Gâthâs and much of the other writings of the Zend-Avesta." [p. 203.]

"I think that neither Spiegel’s nor Haug’s translation can be correct. One thing is certain, that one or the other of them never translates correctly." [p. 227.]

"Spiegel’s translation of this verse is nonsense, pure and simple. Haug’s makes sense, but the wrong sense, and a worthless sense." [p. 232.]

"But there are distressing doubts as to the meaning of a vast number of passages in the Veda, and even of whole hymns, and no less doubt as to the meaning of a multitude of words, to give which theor later and modern meaning is simply to caricature the Veda. The translation of

Professor Wilson, is often unintelligible nonsense, and it is very doubtful whether those of Muir and Müller are not often merely conjectural, and colored by special fancies in regard to the dieties and conceptions of the Vedic Aryans." [p. 97.]

"I doubt the correctness of the translation, and the soundness of the interpretation. I do not believe that there is one allusion to a future existence or another world in the Veda, and not one in the Avesta, where the commentators and translators find ten." [p. 302.]

"I need not point out the absurdities of this translation." [p. 313.]

Repeatedly deprecating the work of the translators and scholars who have interpreted the Avesta, Pike also interjects his own remarks and ideas on race, religion, politics and evolution:

"If everything is to be cramped and contorted to correspond with, or be made to yield to the absurd idea of the unity of the human race, i. e., the descent of all mankind from one man and one woman, by means of incestuous intercourse, inquiry as to pre-historic facts is utterly useless." [p. 35.]

Pike interchanges Aryan to refer to both language type and race, and disparages Darwin’s "natural selection". [p. 65.]

"Why should we suppose that [the creative power of Nature or the Deity] has not, in the same manner, created at different periods the different varieties of the human race, each race, created after another, excelling it?" "Neither history nor tradition informs us of the changes of any white race into negroes, and it is impossible. And for my own part, I am glad to believe that there is no tie of blood-relationship between myself and the wooly and olio negro. I prefer to believe that I am of a higher and nobler strain and race" [p. 66.]

"I do not believe in the possibility of the descent or outgrowth of all languages from one." "Darwin’s notion of the development of men from apes is not a whit more rational." [p. 82.]

"The supreme chief was probably elected as the Germano-Aryans elected their kings, by the acclamations of the armies. No one knows how some of the American Indian tribes elect or select their chiefs. Perhaps, as the bees do their queen. But, in some way or other they succeed in selecting their wisest and best men; a faculty of which civilization seems to deprive mankind." [p. 579.]

"Races and creeds degenerate alike. The old Aryan, Persian, Grecian, Roman and Teutonic nobleness of race has become what the gods regret having created, in more than one modern land. Instead of the noble and heroic rulers of the old simple ages, we have too often the low, the vulgar and the ill-bred, the sordid, mercenary and venal, in republics which always decay into intellectual decrepitude and tawdry vulgarity; and the mildewed and worm-eaten scions of royalty in kingdoms. And even so, as Vedaism rotted into the rankness of Brahmanism, and the Zarathustrian faith into Magism and the worship of the swarming gods of the aborigines, has the doctrine of Jesus, the Essenian Reformer, pure and simple morality, moulded and dry-rotted into effete Romanism, Methodism, and another hundred fungoid excretions; while the pulpit has become, too commonly, the stage for the cassocked histrio and mime, the tribune of the political pimp and termagant." [pp. 100-01.]

"We find, also, here, full proof that the pure were the Aryans, all of them. It is not to be supposed that they were all pure, in our sense of that word, but they were all of the pure blood, and of the pure faith." [p. 268.]

"Masses and thanksgiving always celebrate victories, and parsons who in time of Civil War steal the plate of the communion service from rebellious churches and convey it northward, thank God very devoutly for victories in war and triumphs achieved by means of all possible scoundrelisms in elections.

"Of course we must still have the old Aryan notion of the vast efficacy of prayer, or we would not be willing to pay a larger aggregate tax to those who pray for us, than to those who govern us," [p. 383.]

By pushing the date of the Gâthâs back to 2800 BCE and that of Zaruthustra to 5000BCE, and by forcing his own interpretation on to the Avesta, Pike is also able to justify his claims for a religious unity between Christianity and Zoroastrianism while also depreciating any Jewish influence. Several times Pike points out the Aryan roots of Christianity and deprecates the Semitic. [p. 386.]

"The world owes all its correct and profound conceptions of the Deity, and its knowledge of the existence of the human soul, to the great Aryan race." [p. 100.]

"It is pleasant to know that there was a time once, seven thousand years ago, perhaps, when those of our blood and kin believed, contrary to the modern faith, that nations do not prosper by wrongdoing, nor truly greaten by lies." [p. 420.]

"And also we may well and justly be gratified, that our Aryan race owes its code of morals, as little as it owes its theosophy, religion and philosophy to the Semitic race." [p. 421.]

Pike concludes his text with a short history of the early Christian church and manages to entangle the ideas of Zarathustra—as Pike has extracted them from the Avesta—with the Arian heresy of Arius. [p. 624.]

Neither the Avesta nor Pike’s interpretation have been described in this paper, the purpose being merely to add detail to Pike’s expression of personal beliefs. They are laid out here neither to condemn nor to lionize the memory of Albert Pike but merely for historical accuracy. All quotes are taken from Irano-Aryan Faith and Doctrine as Contained in the Zend-Avesta 6.

ZOROASTRIANISM

Zarathushtra, or Zarathustra, or (from the Greek) Zoroaster was born near what is now Tehran, possibly around 628 BCE, living until around 551 BCE. Some writers place him around 1,200 BCE, while Pike echos the thinking of other 19th century authors by placing him as early as 2,200 to 3,600 BCE. 7. Zarathustra taught a monotheistic faith combined with a belief in a personified duality of good and evil. This latter tendency evolved into the accepted orthodoxy. "Zoroastrian worship is most distinctively characterized by tendance of the temple fire." 8. During the 8th to 10th centuries CE, Islam drove most Zoroastrians into either conversion or flight to the area of Bombay, India.

The prophet Zarathushtra, son of Pourushaspa, of the Spitaman family, is known to us primarily from the Gâthâs, seventeen great hymns which he composed and which have been faithfully preserved by his community. These are not works of instruction, but inspired, passionate utterances, many of them addressed directly to God; and their poetic form is a very ancient one, which has been traced back (through Norse parallels) to Indo-European times. It seems to have been linked with a mantic tradition, that is, to have been cultivated by priestly seers who sought to express in lofty words their personal apprehension of the divine; and it is marked by subtleties of allusion, and great richness and complexity of style. Such poetry can only have been fully understood by the learned; and since Zoroaster believed that he had been entrusted by God with a message for all mankind, he must also have preached again and again in plain words to ordinary people. His teachings were handed down orally in his community from generation to generation, and were at last committed to writing under the Sasanians, rulers of the third Iranian empire [3rd century CE]. The language then spoken was Middle Persian, also called Pahlavi; and the Pahlavi books provide invaluable keys for interpreting the magnificent obscurities of the Gâthâs themselves." 9.

|

|

Aryan (from Sanskrit arya, "noble"), a people who, in prehistoric times, settled in Iran and Northern India. From their language, also called Aryan, the Indo-European languages of South Asia are descended. In the 19th-century the term was used as a synonym for "Indo-European" and also, more restrictively, to refer to the "Indo-Aryan languages (q.v.).

During the 19th century there arose a notion—propagated most assiduously by the Compte de Gobineau and later by his disciple Houston Stewart Chamberlain (qq.v)—of an "Aryan race." Those who spoke Indo-European languages, who were considered to be responsible for all the progress that mankind had made and who were also morally superior to "Semites," "yellows," and "blacks." The nordic, or Germanic, peoples came to be regarded as the purest "Aryans." This notion, which had been repudiated by anthropologists by the second quarter of the 20th century, was seized upon by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis and made the basis of the German government policy of exterminating Jews, Gypsies, and other "non-Aryans." 10.

|

|

ARYANISM

The development of aryanism as a theory of racial superiority is ascribed to Joseph Arthur, comte de Gobineau [Graf von Gobineau] (1816/07/14 - 1882/10/13), who argued the superiority of the nordic races in his work Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines (1853), using skull size as the basis of his argument that whites were superior. A proponant of Gobineau’s theories was Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855/09/09 - 1927/01/09) whose Die Grundlagen des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts (1899) promoted the superiority of the germanic race. They may have been influenced by Geoffrey of Monmouth’s 12th-century history which attempted to single out the Celts as receivers of the world’s destiny.

Gobineau’s works are not found in Albert Pike’s library—or that part of it that has survived—and Chamberlain didn't publish until after Pike’s death so there is nothing to suggest that Pike was aware of, much less promoted, their theories. There also does not appear to be any significance to the publication of Irano-Aryan faith and doctrine in 1924, during the height of Simmons' Klan revival. Regardless, any significance would reflect on the text’s transcriber, M. W. Wood, and not Pike.

|

1. Frontispiece, Irano-Aryan Faith and Doctrine As Contained in the Zend-Avesta, Albert Pike, 1874. Louisville : The Standard Printing Co., 1924. [glued plate: Copyright 1924, by The Supreme Council, 33°, Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, for the Southern Jurisdiction of the United States of America.] transcribed by M.W. Wood, September, 1924. map, 2 frontispiece illusts. HB. 17cm x 26cm. ix, 624 p. lxx glued in frontispiece map, "Imperium Persicum."

Frontispiece, Irano-Aryan Faith and Doctrine As Contained in the Zend-Avesta, Albert Pike, 1874. Louisville : The Standard Printing Co., 1924. [glued plate: Copyright 1924, by The Supreme Council, 33°, Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, for the Southern Jurisdiction of the United States of America.] transcribed by M.W. Wood, September, 1924. map, 2 frontispiece illusts. HB. 17cm x 26cm. ix, 624 p. lxx glued in frontispiece map, "Imperium Persicum."

2. Indo-Aryan deities and worship as contained in the Rig-Veda, Albert Pike, 1872. Louisville, Standard printing, 1930. ix, [3], 650 p. illus. (incl. chart) pl., diagrs. 26 cm. LCCN: 30024322 ; Lectures of the Arya [by] Albert Pike, 1873. Louisville, Ky., The Standard Printing Co., incorporated [c1930] 3 p. l., 340 p. 26 cm. LCCN: 30024323 Irano-Aryan faith and doctrine as contained in the Zend Avesta, [by] Albert Pike, 1874. Louisville, The Standard printing co., 1924. 2 p. l., ix, 624, ixx p. front. (fold. map) 2 pl. 26 cm. LCCN: 25002566. Indo-Aryan deities and worship as contained in the Rig-Veda, Albert Pike, 1872. Louisville, Standard printing, 1930. ix, [3], 650 p. illus. (incl. chart) pl., diagrs. 26 cm. LCCN: 30024322 ; Lectures of the Arya [by] Albert Pike, 1873. Louisville, Ky., The Standard Printing Co., incorporated [c1930] 3 p. l., 340 p. 26 cm. LCCN: 30024323 Irano-Aryan faith and doctrine as contained in the Zend Avesta, [by] Albert Pike, 1874. Louisville, The Standard printing co., 1924. 2 p. l., ix, 624, ixx p. front. (fold. map) 2 pl. 26 cm. LCCN: 25002566.

3. Encyclopaedia Britannica. vol.12. 15th edition. Chicago: 1989. p. 936.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. vol.12. 15th edition. Chicago: 1989. p. 936.

4. "The original manuscript of his Irano-Aryan Faith and Doctrine, in three large volumes, written by his hand and with quill pens fashioned by himself, is a prized possession of the Supreme Council. As a tribute to his memory and to add to the world’s store of knowledge, the Supreme Council ordered that an edition De Luxe of fifty copies and a cloth edition of one thousand copies be printed." Irano-Aryan Faith and Doctrine, loose sheet 13 x 21.5 cm accompanying cloth edition, rebound by University of Washington. 15.5 x 24 cm.

"The original manuscript of his Irano-Aryan Faith and Doctrine, in three large volumes, written by his hand and with quill pens fashioned by himself, is a prized possession of the Supreme Council. As a tribute to his memory and to add to the world’s store of knowledge, the Supreme Council ordered that an edition De Luxe of fifty copies and a cloth edition of one thousand copies be printed." Irano-Aryan Faith and Doctrine, loose sheet 13 x 21.5 cm accompanying cloth edition, rebound by University of Washington. 15.5 x 24 cm.

5. The Avesta was translated by James Darmesteter [1849-1894] and L.H. Mills in Sacred Books of the East, [Friedrich] Max Müller (ed.). vols. IV (The Zend-Avesta, part 1), XXIII (The Zend-Avesta, part 2), XXXI (The Zend-Avesta, part 3). LCCN: 32011950. Vedic hymns. Translated by F. Max Müller . Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1891-97. 2 v. 23 cm.. A digital edition of James Darmesteter’s translation of the Avesta is available at <avesta.org/avesta.html>. Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil du Perron [1731-1805] erroneously called it the Zand-Avesta, not realizing that the Zand was a commentary added by the Sassanids.

The Avesta was translated by James Darmesteter [1849-1894] and L.H. Mills in Sacred Books of the East, [Friedrich] Max Müller (ed.). vols. IV (The Zend-Avesta, part 1), XXIII (The Zend-Avesta, part 2), XXXI (The Zend-Avesta, part 3). LCCN: 32011950. Vedic hymns. Translated by F. Max Müller . Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1891-97. 2 v. 23 cm.. A digital edition of James Darmesteter’s translation of the Avesta is available at <avesta.org/avesta.html>. Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil du Perron [1731-1805] erroneously called it the Zand-Avesta, not realizing that the Zand was a commentary added by the Sassanids.

6. Irano-Aryan Faith and Doctrine as Contained in the Zend-Avesta. Irano-Aryan Faith and Doctrine as Contained in the Zend-Avesta.

7. A commonly given date is the seventh century BCE, although Humbach discounts this date. (Gathas 1991 p. 30). Boyce’s thinking has ranged from 1,000 BCE (1975), to 1,700 BCE (1979), and has settle on 1,200 BCE as the more likely (1992). Bruce Lincoln notes "At present, the majority opinion among scholars probably inclines toward the end of the second millennium or the beginning of the first, although there are still those who hold for a date in the seventh century." (Death, War, and Sacrifice, 1991, p. 150). Humbach and Ichaporia favour 1,080 BC but mention the 630 date. (Heritage, 1994, p. 11). Cf.: Bruce Lincoln, Death, War, and Sacrifice; Flattery, David and Martin Schwartz, Haoma and Harmaline, 1989 ; Jacob Neusner, Judaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism in Talmudic Babylonia, 1986 ; Kreyenbroeck, Srosha in Zoroastrian Tradition ; Boyce, Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism, Wisdom of the Sasanian Sages ; Bailey, Zoroastrian Problems in 9th Century Books ; Zaehner, Teachings of the Magi ; Zaehner, Zurvan A Zoroastrian Dilemma, Oxford 1955.

A commonly given date is the seventh century BCE, although Humbach discounts this date. (Gathas 1991 p. 30). Boyce’s thinking has ranged from 1,000 BCE (1975), to 1,700 BCE (1979), and has settle on 1,200 BCE as the more likely (1992). Bruce Lincoln notes "At present, the majority opinion among scholars probably inclines toward the end of the second millennium or the beginning of the first, although there are still those who hold for a date in the seventh century." (Death, War, and Sacrifice, 1991, p. 150). Humbach and Ichaporia favour 1,080 BC but mention the 630 date. (Heritage, 1994, p. 11). Cf.: Bruce Lincoln, Death, War, and Sacrifice; Flattery, David and Martin Schwartz, Haoma and Harmaline, 1989 ; Jacob Neusner, Judaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism in Talmudic Babylonia, 1986 ; Kreyenbroeck, Srosha in Zoroastrian Tradition ; Boyce, Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism, Wisdom of the Sasanian Sages ; Bailey, Zoroastrian Problems in 9th Century Books ; Zaehner, Teachings of the Magi ; Zaehner, Zurvan A Zoroastrian Dilemma, Oxford 1955.

8. Zoroastrians, Their religious beliefs and practices,, Mary Boyce. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London: 1979. p. 17. Also see A Guide to the Zoroastrian Religion, Firoze M. Kotwal and James W. Boyd. Scholar’s Press: 1982. A nineteenth century catechism by Erachji S. Meherjirana, with translation and commentary by a modern Dastur (high priest).

Zoroastrians, Their religious beliefs and practices,, Mary Boyce. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London: 1979. p. 17. Also see A Guide to the Zoroastrian Religion, Firoze M. Kotwal and James W. Boyd. Scholar’s Press: 1982. A nineteenth century catechism by Erachji S. Meherjirana, with translation and commentary by a modern Dastur (high priest).

9. Encyclopaedia Britannica vol 1,15th edition. Chicago: 1989. pp. 611

Encyclopaedia Britannica vol 1,15th edition. Chicago: 1989. pp. 611

10. Encyclopaedia Britannica vol 1, pp. 738-39.

Encyclopaedia Britannica vol 1, pp. 738-39.

|

|