|

|

|

Revealed:

The secret of Oak Island

by Laverne Johnson

|

SPECULATIONS

SPECULATIONS

|

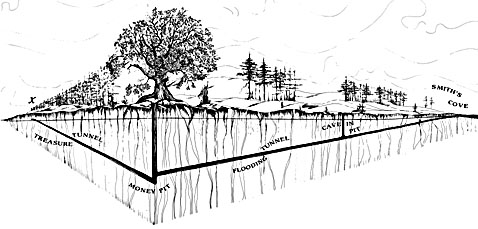

The mastermind who planned the deposit had no alternative regarding the manner in which he buried his treasure. If he expected to retrieve it he had to leave it at or above sea level. It was obviously of sufficient mass that he could not possibly conceal it in such a way that there would be no evidence left of somebody having buried something there. Many burrowing animals dig down to remarkable depths and then tunnel up to a point near the surface to make their nests. Such a plan was ideal for the depositor. He would dig a deep shaft, and then tunnel from its depths outward and upward into the high ground above sea level and some distance from the shaft. There was almost no limit to the amount he could cache up in that high ground, and such a depository made recovery relatively simple. If he could return, all he had to do was to locate the correct spot, dig down to a point not below sea level where his deposit was lying high and dry; safe from the flooding water, or from chance searchers. To guarantee, beyond any shadow of doubt, that chance searchers would not clean out his shaft and follow the treasure tunnel up to the deposit, he simply dug a tunnel out to Smith’s Cove, and let the Atlantic Ocean into the depths of his workings. As far as the depositor was concerned that flooding water sealed off the depths from everybody for all time.

The depositor had to set up some kind of inconspicuous system that would tell him, if and when he could return, precisely where he would have to dig the shallow shaft that would take him down onto his safely stored treasure. To a man like the depositor, devising such a system would not pose any problem. He set up a system or a code that could very well have been discovered at any time after 1795 if the searchers had not been so eager to get to the bottom of the shaft, and then in 1849 had not been so intrigued by the drillers' reports of all that metal in pieces that they had drilled through down in the depths.

There is no report of anybody scouring the eastern end of the Island for some sign of a code, and it was not until the end of the nineteenth century when a drilled stone north of the Money Pit and a large stone triangle far south of the Money Pit were reported. Even then they were not recognized as possibly being part of a code. It was not until 1937 that the marks were pinpointed by a survey, and it was another twenty-two years more before they were recognized for what they were.

Through the years there have been unconfirmed reports that hint at some possibility of a tunnel between the Money Pit and the cove on the south shore. People have asked why the depositor would drive a five hundred foot tunnel out to Smith’s Cove when he could have settled for a three hundred foot tunnel to the south shore. It is quite possible that he made a judgement error in his original plan. It could be that he originally intended to run his tunnel out to the south shore, but that something happened to make him change his mind after he started work on it. Perhaps he came to realize that the south shore was too exposed to the storms that drove in past the Tancook Islands and pounded on the south shore of Oak Island. Perhaps a strange ship came sailing part way up into Mahone Bay, and he realized that there was too much danger of their being seen if they worked on the south shore, or perhaps he learned that he would have water problems if he tried to tunnel to the south shore. Of course none of this is at all important as regards the recovery of the treasure, but it is very unlikely that a tunnel from the south shore came anywhere near completion.

Another thing with no importance as regards the recovery of the treasure is the unending conjecture about where the ship that brought the treasure came from. It is too much to suggest that the Norsemen could have done the work at Oak Island. They had disappeared from the Atlantic coast before Columbus came to America. The native red oaks like the one that first drew attention to the treasure site have a life span of about two hundred and fifty years, according to Nova Scotian foresters, so the Norsemen were long gone when the tree at the Money Pit sprouted. It is equally irresponsible to suggest that the Incas, with all those rugged mountains close to home would carry their treasure through hundreds of miles of Spaniard infested seas to deposit their gold on an island in an area that they had never heard of.

The ship that came to Oak Island carried a large amount of coconut fibre, which would indicate that it likely came from a place where coconut fibre was commonplace. The most likely source would have to be the Central American area. The large amounts of coconut fibre have often been explained by saying that the fibre was commonly used as ship’s dunnage or packing for stowing ship’s cargo. One might be tempted to ask, "For what kind of cargo?" Heavy material such as containers of gold or silver are very weighty and must be lashed or shored solidly in place so they cannot shift and wreak havoc to the hull of a rolling sailing vessel. But for packing something fragile the coconut fibre could make very acceptable dunnage.

Ships leaving Central America and heading for Europe usually came out of the Straits of Florida and swung north to ride with the Gulf Stream up to a latitude north of Bermuda. There they caught the Westerly winds, and those winds and the weakening Gulf Stream made the easterly crossing much easier. At one point the nearest land would be Nova Scotia, and a crippled ship might well drift, or be blown, or work her way in to a landfall on Nova Scotia’s south shore. Such a ship must have come to Oak Island.

Investigating some of the cargos of other sailing ships in those years makes it interesting to speculate about what a part of the cargo of the Oak Island ship may have been. For instance, in 1985 Captain Hatcher salvaged the wreckage of the Dutch East Indiaman, Geldermalson, from the reef in the South China Sea where she had been wrecked in 1752, (Reader’s Digest, November 1986). Her shipping papers were still extant in Holland, and showed that part her cargo consisted of 55 kg. of gold and 239,000 pieces of Chinese Porcelain packed in 348 tonnes of tea. The National Geographic tells us that Chinese Porcelain was brought across the Pacific in the Manila Galleons and trans-shipped to Europe, and it has been reported packed in petuntse (the clay from which it was made), in tea and in peppercorns. They have no reports of it being found packed in coconut fibre, but agree that it could have been packed in the fibre if it had been convenient, before it was dispatched to Europe. Mrs. Mildred Restall, whose husband and older son were killed in an accident at Oak Island in 1965, used to have some broken pieces of china which had been recovered from the workings by her men. She never had them identified or classified, and no longer has them, but if any of them were Chinese Porcelain it could be an indication of what that coconut fibre found at Oak Island had been used for.

Probably we will never learn how the group left Oak island, or whether any of them survived. There is at least one story which hints that somebody must have got away and lived long enough to leave a plan or report of what happened on the Island. It comes to us third hand, and is known as the Spanish Sailor story. It would appear to have been told around the middle 1800s, and it tells about a plan which shows an island somewhere on the Nova Scotia coast where a large treasure was buried. The most interesting thing about the story is its explaining that there is a deep filled in shaft on the island, and that there is a long tunnel running from the shaft out to the shore. It goes on to say that for some reason unknown to the story teller the treasure was not buried in the shaft, but some distance away and only twenty feet deep. It may have been told before the flooding tunnel out to Smith’s Cove had been discovered, and it was certainly told before anyone had suggested that the treasure was buried some distance from the shaft, and that it was buried above sea level. If there is any truth in the tale, the story teller must have been from a later generaton than the depositors. No attempt was made to capitalize on the story, and now it is an almost forgotten tale that could have been connected with The Oak Island Mystery.

We can only conjecture as to how the group left the island. They may have repaired their crippled ship to some extent, and sailed away in her, and have been lost at sea. They may have taken timber from her and from the forests in the area, and built a smaller vessel, and tried to get away in that fashion. If they were Spaniards they may even have tried to walk back south toward their own people, all the way from Nova Scotia to the Gulf of Mexico. Life was hard in those times, and that possibility is not as far fetched as it would seem to be.

In 1568 John Hawkins and Francis Drake raided the Spaniards in the Gulf of Mexico, and they lost the battle. Drake, thinking that all was lost, left the battle and returned to England with his ship and crew. John Hawkins lost his big ship, the Jesus of Lubeck, but managed to take her survivors aboard his remaining smaller ship and get away from the Spaniards. He had too many men aboard to risk trying to cross the Atlantic when he was so overburdened, and he was forced to put one hundred and fourteen men ashore on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. The Indians and Spaniards killed most of them, but twenty three escaped and fled north to get away from their enemies, and perhaps hoping to encounter an English ship farther north. About sixteen months later the three sole survivors of that group were picked up by a French ship on the coast of Nova Scotia, and they swore that they had walked all the way from the Gulf of Mexico. Their names were David Ingraham, Richard Browne, and Richard Twide. When they got back to England their stories were received with a good deal of scepticism, and a considerable investigation was conducted. Hawkins eventually agreed that they were three of the men he had marooned, and their feat is recorded in history as the Impossible Walk or the Long Walk. It is conceivable that the men from Oak Island attempted to make a similar walk.

|

|